#10 China, At Last

I started learning Chinese in the spring of 2020, only a few weeks before...well, you know. I did it mostly on a whim, thinking that if I could keep at it for a month or two, maybe I could be a more empathetic or, at least, better informed journalist. I never imagined that Chinese, or China itself, would become a core part of my professional life. But once that became clear, I knew without a doubt that I had to go to China.

There's an arrogance in assuming that one or even several trips to a place can give you the full measure of it. I've written about this idea before in relation to Taiwan, but it's even more true in China, a sprawling country of 1.4 billion people with almost mind-numbing diversity. Knowing that, I still wanted to use my year abroad in Asia to find a way into China. Hopefully, it would be the first of many trips, but with U.S.-China tensions being what they are, one can never assume it'll be easy to return.

So, I made it my mission to get a China visa and find my way there during my year studying in Taiwan. Last weekend, I finally made it, spending four days in Nanjing with my classmate Sina. I want to begin by first talking about why I chose Nanjing as the first place to visit. It's impossible to write about my experience without including the heart of my trip, which was to the Nanjing Massacre memorial.

Then, I have some more scattered thoughts about the feeling of being a foreigner in China. Despite my limited experience in China, I get the sense that the experience has changed quite a bit since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. (And please, I'm curious to hear any thoughts or reactions from readers who are either from China or have spent time there.)

Why Nanjing?

I'm the kind of boring tourist who loves exploring historical monuments and spending time in museums. In that sense, Nanjing is a perfect fit. The city, whose name means "south capital," served as the capital of the Ming dynasty, Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (oh boy, Google that please), and the Republican government under Chiang Kai-shek. If you know anything about Chinese history, you know that none of these entities enjoyed a happy ever after.

Nanjing remains best known for the horrific massacre that followed Chiang's forces' retreat. Japanese invaders, upon taking control of the city, proceeded to plunder its people, killing thousands of civilians. (By China's official count, the death toll is 300,000. Japanese and Western scholars estimate a bit less, though I tend to subscribe to historian Daqing Yang's argument that "an obsession with figures reduces an atrocity to abstraction and serves to circumvent a critical examination of the causes of and responsibilities for these appalling atrocities.")

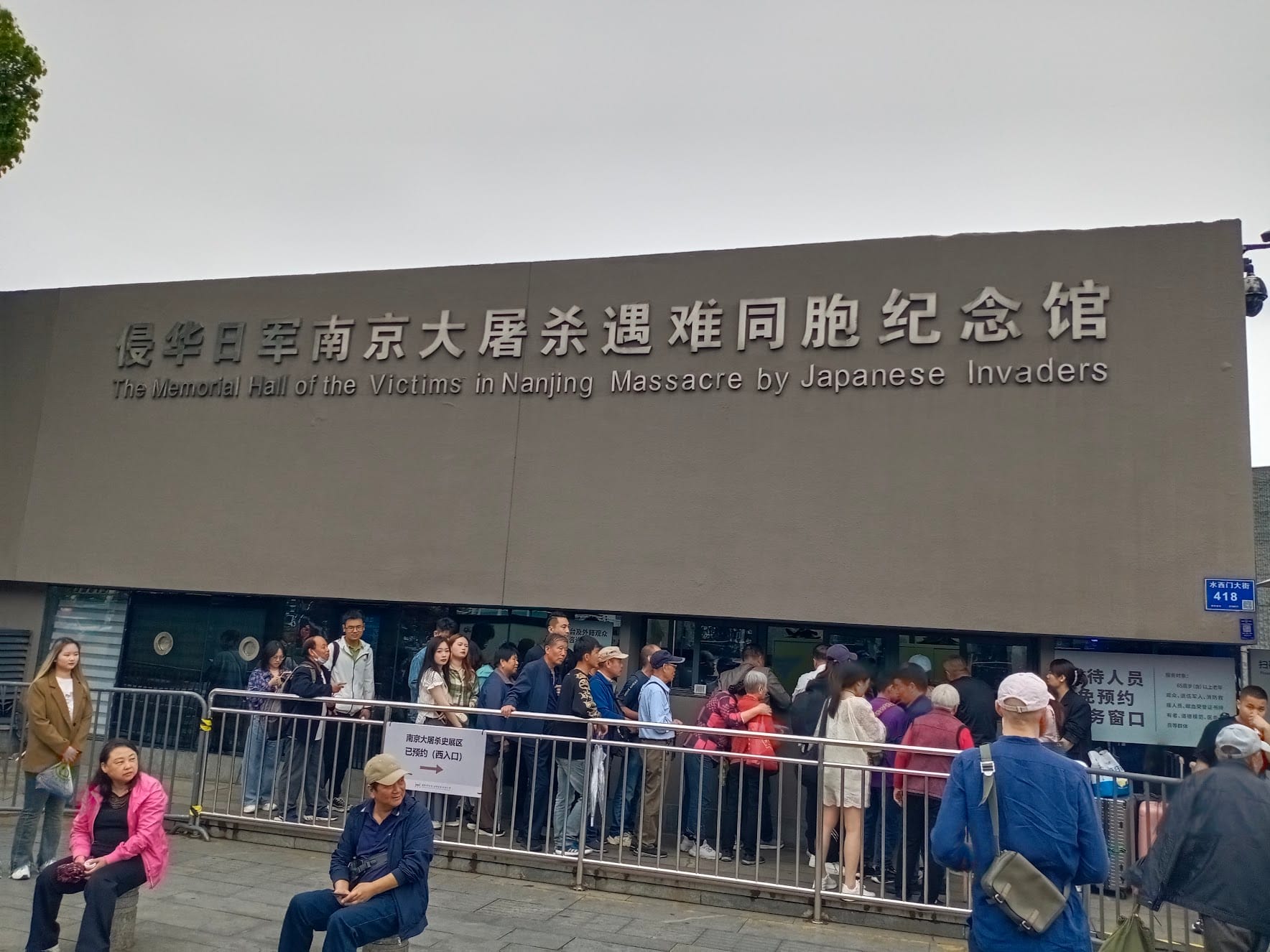

What remains indisputable is the Nanjing Massacre is one of the darkest moments of World War II and a core part of the city (and China's) cultural memory. The city's sprawling memorial to the victims of the massacre, on the day I went, was crowded with tourists, many of whom were schoolchildren from neighboring provinces. Others came from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau—all united, no doubt, by a shared sense of horror at the actions of Japanese troops in Nanjing.

While at the museum and memorial, it was hard not to compare it with my experience in Hiroshima, the site of another World War II-era catastrophe. In Hiroshima, I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness for the lives lost, but little in the way of anger toward the United States or repentance for Japan's own wartime-era crimes. Though of course there are political reasons for this sentiment—the United States went on to occupy Japan and later become its staunchest ally—but, at the time, I found it entirely appropriate. In a previous newsletter, I wrote, "Hiroshima's tragedy has many authors, but it's still a tragedy. No matter the context, we can and still mourn what the bomb did."

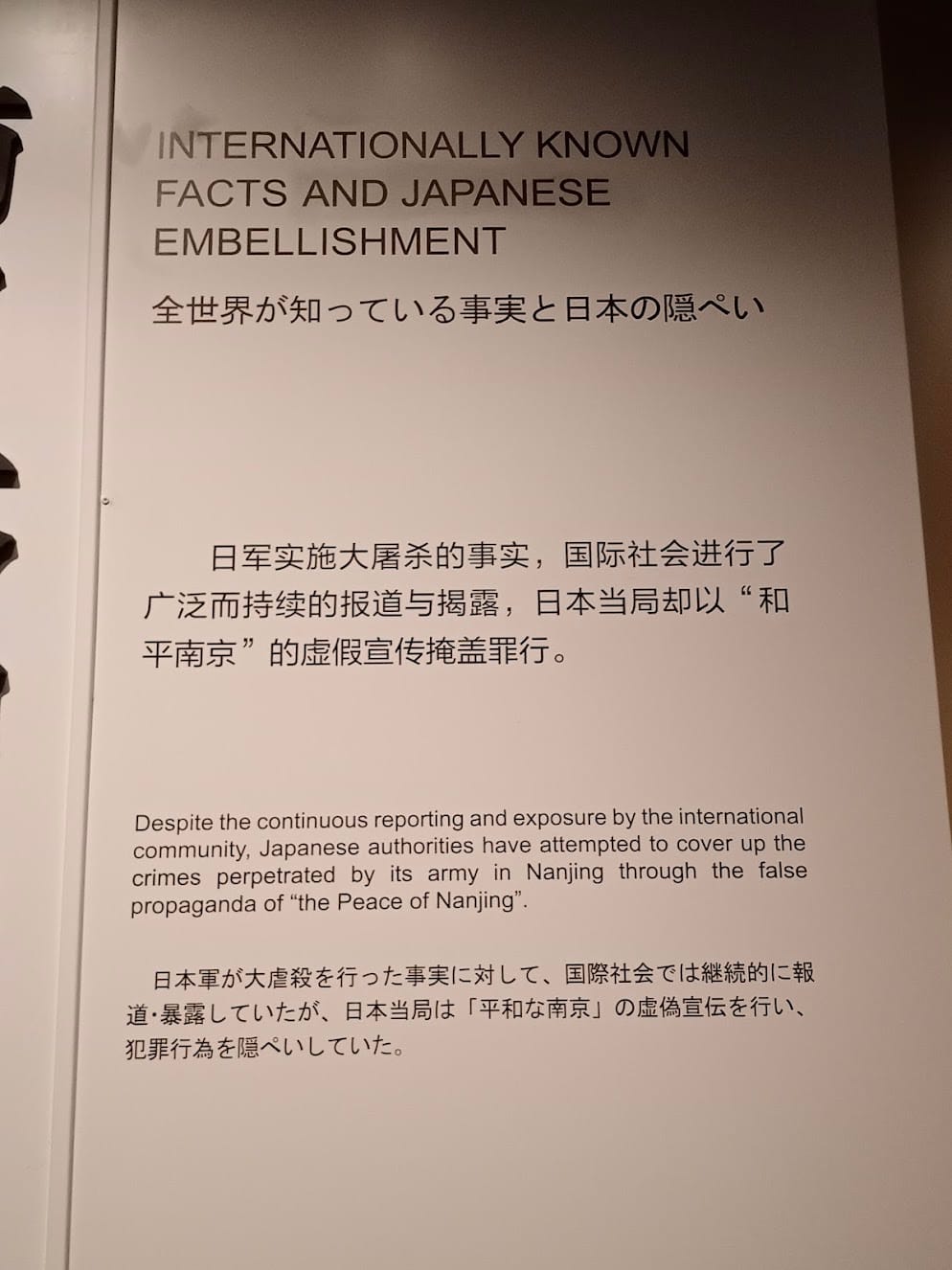

I still believe that, but the Nanjing Massacre offers a particularly potent repost to the idea that we can mourn tragedies without fixating on the perpetrator or their motive. Throughout the memorial are clear reminders of Japanese culpability and, more powerfully, consistent efforts by the Japanese press before and since to downplay or outright deny the massacre.

It is no surprise that China today holds the most broadly negative view of Japan of any nation on Earth, more negative even than in South Korea (another country with a long memory of Japanese wartime atrocities). Japanese people also harbor deeply negative views of China. Here's a remarkable statistic: China is viewed more as a threat in Japan than in Taiwan, a place China is actively attempting to annex.

Every aspect of the museum—from its very name to the sequence of exhibits—points not only to the horror of the massacre, but enduring anger over Japanese culpability.

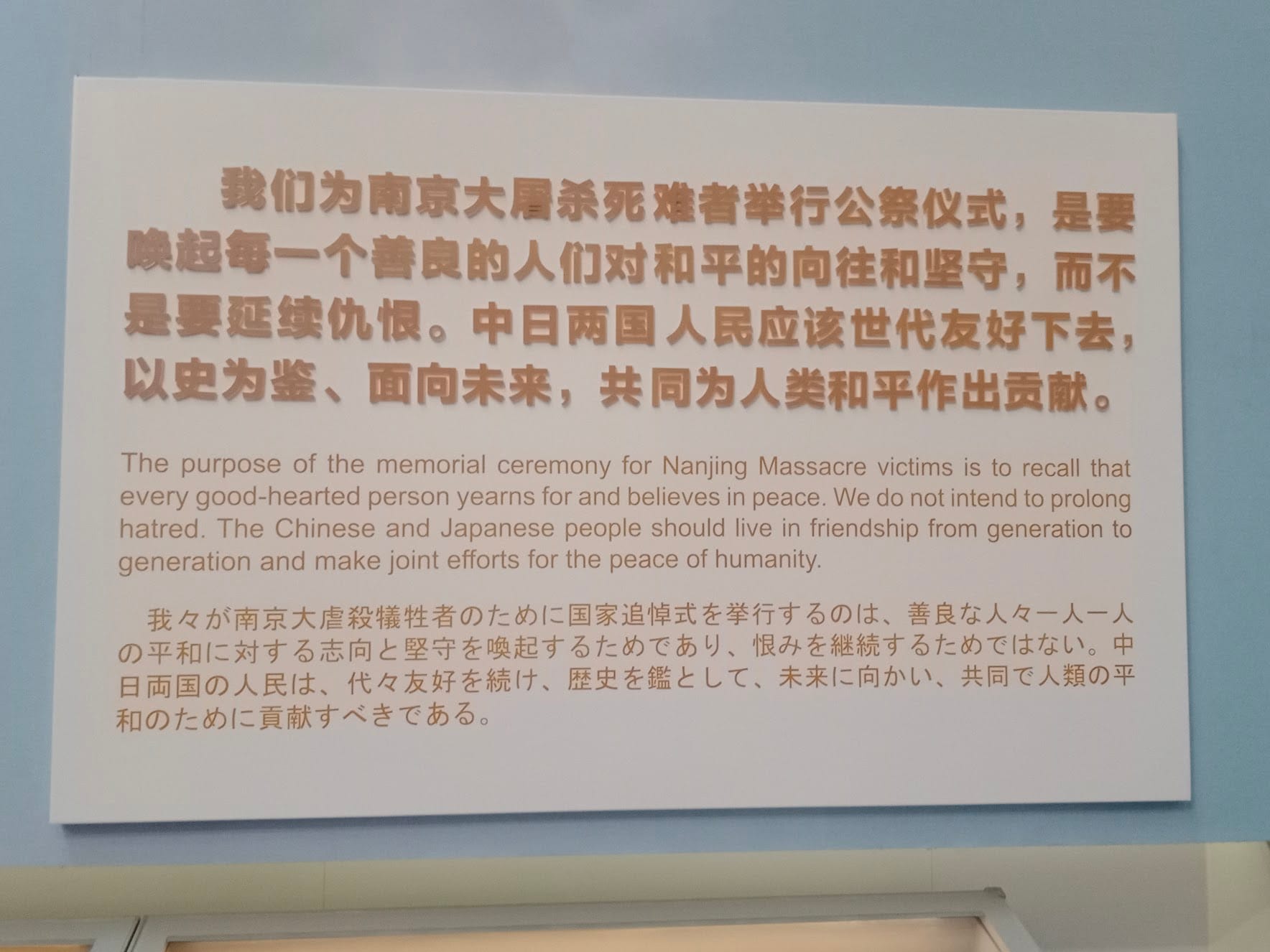

Near the end of the museum, as a postscript of sorts, is an inscription seeking to soften the tone of the preceding exhibits. When I was reached this part of the museum, a woman next to me began reading it aloud—for the benefit of her young son, who probably could not read the Chinese characters. It's a beautiful message and felt, honestly, inspiring to hear out loud at the end of a tour of the worst of humanity.

This period of Chinese history (not to mention the current fraught state of Sino-U.S. relations) does not inspire much in the way of optimism. But any sliver of hope for peace, reconciliation, and understanding is worth fighting for. And it was with that conflicted set of emotions, I left the memorial.

"Hey, can I take a picture with you?"

When I read Peter Hessler's book River Town (a book I've praised before in this newsletter) about his time teaching English in the small city of Fuling in Sichuan province, I was struck by how he described the fear of going out into the city as a foreigner.

When I walked down the street, people constantly turned and shouted at me. Often they screamed waiguoren or laowai, both of which simply meant “foreigner.” Again, these phrases often weren’t intentionally insulting, but intentions mattered less and less with every day that these words were screamed at me. Another favorite was “hello,” a meaningless, mocking version of the word that was strung out into a long “hah-loooo!” This word was so closely associated with foreigners that sometimes the people used it instead of waiguoren—they’d say, “Look, here come two hellos!” And often in Fuling they shouted other less innocent terms—yangguizi, or “foreign devil” da bizi, “big nose”—although it wasn’t until later that I understood what these phrases meant.”

Since coming to Taiwan, I never had a single experience even remotely comparable to this, not even in more rural parts of the island. Occasionally, a young kid would point and say, “Waiguoren!" but, more often than not, Taiwanese people would seem completely unplussed by my being a foreigner and, maybe, slightly impressed upon learning I could speak Mandarin.

Well, once I spent some time in Nanjing, I had a better sense of what Hessler meant. Sina and I could not go to a single public place without being deluged with requests for selfies or at least courting persistent stares. At the Nanjing Imperial Examination Museum, which is in one of the busier, more touristy areas of the city, the requests for selfies got so out of control that we actually had to leave the museum! (Thankfully, a staffer let us back in a few hours later for free.)

To most foreigners, I imagine the attention from locals is funny or, at least, somewhat charming. When it came from a kid—as when a toddler waddled over to me in the park and screamed, "WAI GUO REN!"—it was honestly quite cute. And, to be clear, no one was hostile or cruel to us. But at other times, the attention made me uncomfortable. The way I described it to my parents in a phone call was: I felt like a zoo animal.

I pictured China as a place where I can reasonably get around, ask for help, and communicate decently. In a sense, I imagined that I could blend in. I wouldn't have to lean on Google Translate or speak only to locals who could understand English. What I didn't expect was to feel so foreign, which was again a welcome reminder of how rarely our idea of a place matches to the reality. I'm sure after my next trip to China in June, which is far more ambitious and includes several cities, I'll have an even better idea of how skewed that initial perception was.

What do the "Core Values of Socialism" mean to you?

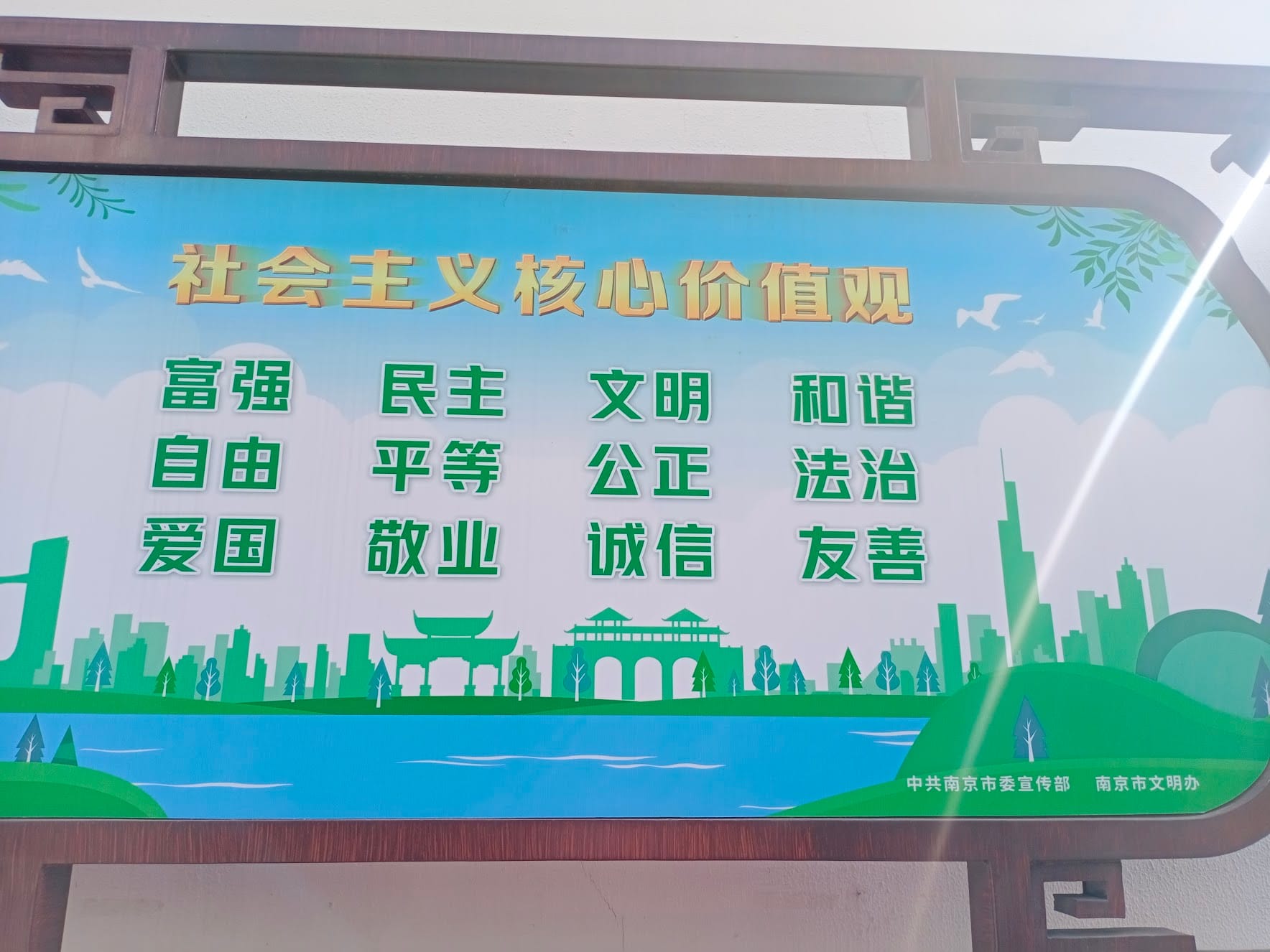

On nearly every street corner in Nanjing, I noticed a sign looking something like this:

The heading of this sign reads: 社会主义核心价值观 (Core Values of Socialism) and promotes a set of values enshrined in 2012 as the Chinese interpretation of socialism. These signs are omnipresent throughout the city: near bus stops, in parks, even in a mosque we visited. They include values like 自由 (freedom) and 民主 (democracy) that no serious academic would associate with Chinese politics while still serving as a reminder that the Party, above all else, sets the standard for Chinese governance and culture.

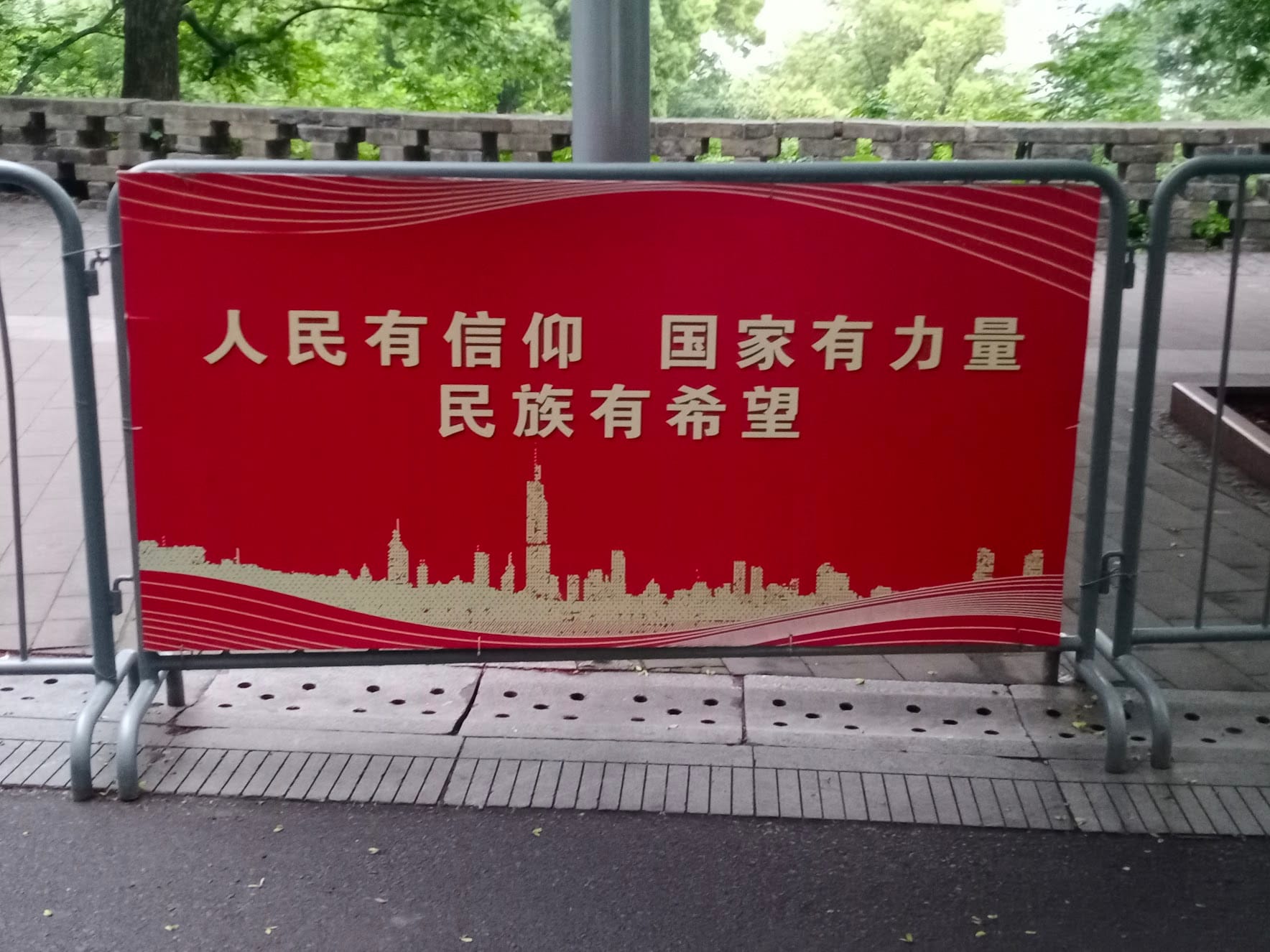

There is a long history of government propaganda in public spaces in China. Nanjing is certainly no different. When I was there, I noticed a few slogans that were fairly benign and even a bit sing-songy.

Take this one, which rhymes:

It reads: 人民有信仰 国家有力量 民族有希望 (Rénmín yǒu xìnyǎng, guójiā yǒu lìliàng, mínzú yǒu xīwàng), which in English, roughly corresponds to "The people have faith, the country has strength, the nation has hope."

A rudimentary understanding of China might lead someone to think the cities are littered with "COMMUNISM ROCKS!" and "ALL HAIL XI JINPING"-style messaging, but the more common strategy I saw was this kind of vague, though staunchly patriotic, signage.

The world's most oddly-placed theme park

On the Monday of my trip, when most museums are closed in China, Sina and I went to the Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs, where several early members of the Chinese Communist Party were killed by Chiang's Chinese Nationalists. The park is absolutely huge, featuring this beautiful centerpiece:

The complex itself also served as a symbol of how politics, national identity, and commerce meet in a fascinating way. In a short walk from that memorial, visitors to the park could spend time at the Martyrs' Execution Site or at this kids' amusement ride, which appears to be an off-brand take on Pirates of the Caribbean (with what looks like Mickey Mouse in the background):

China, like any big country, contains multitudes. That is for sure.

Odds and Ends

1.

While in Hong Kong, where I applied for and ultimately received my China visa, I overheard easily the most infuriating conversation of my life. I want you to imagine the scene: a drab office full of anxiety-ridden travelers, paperwork strewn everywhere, emotions on high. I'm waiting for an attendant to accept my application when a family of three sits behind me. They seem quite nice and fairly calm despite having just gotten off of a several-hour flight. Though they occasionally drift into Chinese, their conversation is mainly in English. And it's in English that I hear them engage in an argument that still haunts me to this day.

The mother, who looks to be in her 50s, is describing a movie she watched on the plane, though evidently she's forgotten the name. "There was a boy, his dream was to run a chocolate factory." Her son, roughly my age, perks up. "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory! That's what you watched." The mom shakes her head. "No, no, his name wasn't Charlie." The son seems confused. "Oh, the little boy's name is Charlie. The guy who owns the chocolate factory is Willy." The mom shakes her head again. "No, Willy is the boy. He only gets the chocolate factory at the end of the movie." The son looks even more confused. "That boy is Charlie! He wins the chocolate factory at the end of the movie."

While this is happening, I realize that they're talking about two different movies: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, based on the Roald Dahl novel, and Wonka, the prequel released this year where Timothée Chalamet plays a younger version of the chocolate factory owner. Inexplicably, neither of them seems to know the existence of the other movie! This argument goes on for at least 10 minutes, testing the limits of my self-control as I consider whether to intervene. By the time my number is called and I carry my documents to the counter, the mom and son are still arguing about what movie she watched. In that moment, I felt like I had witnessed some absurd reprise of Waiting for Godot.

2.

While in a cab in Shanghai, I talked to my driver a bit about the United States and was shocked when he knew "Philadelphia," which in Chinese is 费城 Fèi chéng. His reason? As a kid, he watched a TV show about 富兰克林 Fù lán kè lín — Benjamin Franklin! I proceeded to tell him a joke my Dad loves to say, which is that Ben Franklin is not only the metaphorical "father" of our country, but possibly the literal father too, given his tendency to—shall we say—leave the bounds of his marriage.

As a fun postscript to this story: when I worked at a waterpark in Wildwood, New Jersey during high school, I remember my boss one day found out through Ancestry.com (or a similar service) that he was actually descended from Benjamin Franklin. Truly, a "Founding Father."

I still have a few more newsletters in the works before I leave Taiwan. I deeply appreciate all who have subscribed and continue to read my musings, most of which are not as long as this edition!

Please stay in touch and I urge you to reach out, either on Instagram or by email (dspin3@gmail.com), if you have any thoughts—and, especially, if you think there was anything that I may have gotten wrong in my analysis here.

Wishing you all a wonderful week.

Dan