#9 The One Where I Talk About the Earthquake

Another packed newsletter today, including: a fun Chinese-language-learning story, a crazy travel story, and, oh yeah, that 7.4 magnitude earthquake.

Let's get right into it.

Imagine, just for a moment, that it's a Wednesday morning and you're barely awake. The alarm still fresh in your ears, you lay back for just a few more minutes of sleep when suddenly the room starts shaking. This isn't anything new; you've felt several smaller earthquakes by now and usually after a few seconds, they're over.

But this one is different — your bed and bureau begin to violently shake, scattered belongings fall to the floor, and the noise—of people yelling, wind whooshing, feel far more visceral than before. Then it's over.

Your mind has wandered to the unthinkable—were we just attacked? what the hell was that?—before settling on the obvious: yes, that was a massive earthquake. You check in with your roommates, inspect the damage (just some siding off the wall outside), and regroup. It's time for morning class.

That, in a nutshell, is what I experienced on the morning of April 3. Our brains have a weird way of compartmentalizing crazy events, so when, a few hours later, a slew of concerned friends reached out to check in, I was already thinking about my itinerary for the day: homework, lunch, some errands. But everywhere around me were signs that this earthquake was truly different and would leave a more sizable impact, even though the Taiwanese authorities responded quickly and comprehensively.

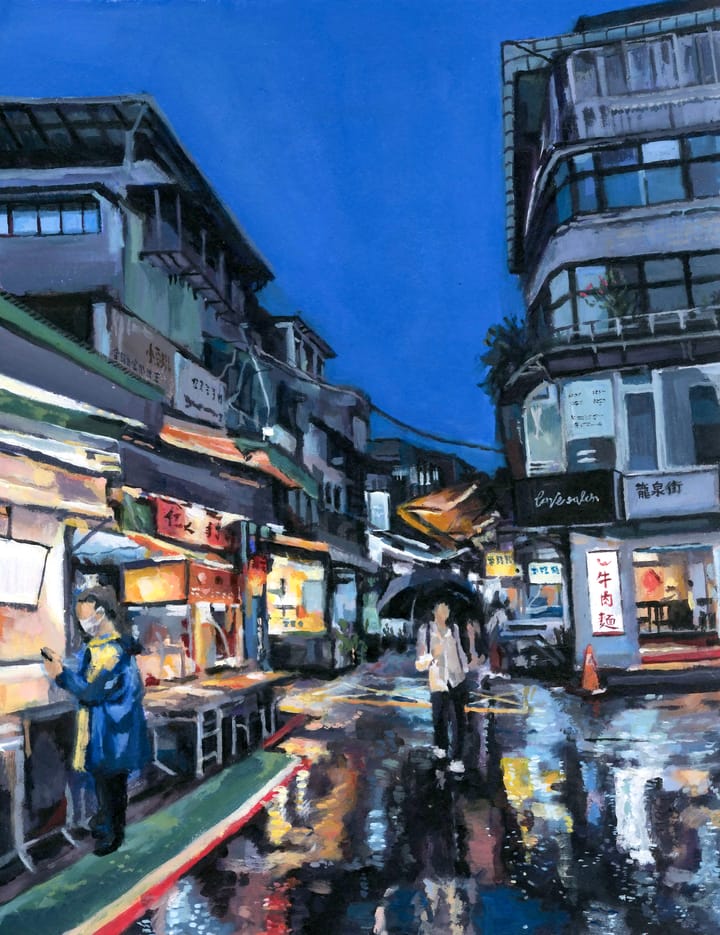

Next door to my apartment, the roof of a beef noodle soup restaurant caved in. While most of the vendors near my apartment were not affected by the earthquake, this shop still hasn't reopened:

In the earthquake's epicenter, the region of Hualien on Taiwan's east coast, the damage was more widespread. But still, it is remarkable how well-prepared Taiwan was for the quake. For context: the last earthquake of a similar magnitude to hit Taiwan was in September 1999, killing 2,400 people and injuring 11,000 more. This time around, only 14 people died, which while still a terrible tragedy, marks a substantial improvement for Taiwan's emergency response.

Another reminder of the earthquake's power is the near-relentless series of aftershocks that continue to pummel the island (and keep many of us awake at night). These aftershocks culminated in more than 80 (!) small quakes earlier this week, turning everyone's Tuesday morning into a dreary slog, though thankfully no one seems to have been hurt.

Traveling to Taiwan's "Island in Between"

Just a day before the 7.4-magnitude earthquake struck Taiwan, I flew back to Taipei from Kinmen, an island administered by Taiwan but located just six kilometers from the Chinese mainland.

Kinmen, known in Chinese as 金門 (pronounced "Jīn mén" and meaning "Golden Gate,") is a curious place, as culturally distinct as any place I've been to in Taiwan. It's as famous for its powerfully strong liquor as it is for being a final frontier of the Chinese Civil War, reminders of which are scattered throughout the island. As the story goes, Mao Zedong's peasant army, which had by 1949 swept through the country and sent the Nationalist Army fleeing to Taiwan, had virtually no experience with maritime combat. Their effort to take Kinmen flopped, a Pyrrhic victory for the flailing Nationalist Army, which nonetheless reconstituted itself in Taiwan and has held control of Kinmen ever since.

Since then, Kinmen occupies a fascinating grey area between China and Taiwan. While reliant on China for its water and flush with commercial ties to the mainland, Kinmen remains under Taiwan's jurisdiction and is full of visual memories of the Chinese Civil War. There are streets full of propaganda messages—"take back the mainland!"—that seem entirely out of place within contemporary Taiwanese politics, where the ruling Democratic Progressive Party has essentially abandoned that long-ago dream and embraced a distinct Taiwanese identity.

One of the more striking examples of Kinmen's wartime memory is the Temple of Li Guang-Qian, a Nationalist general who was killed during the island's ultimately successful repulsion of Mao's forces. While structured like a religious temple, the building is actually a monument to Li's sacrifice and to the Nationalist soldiers who fought on Kinmen. Inscriptions include references to 共匪 (Gòng fěi, "Communist bandits") and serve as a reminder of Kinmen's evolution from a symbol of cross-Strait tension to arguably one of the more "pro-China" places in Taiwan, where Chinese influence abounds and lawmakers are constantly looking to cement business ties with the mainland and attract Chinese tourists.

On that note, I'd be remiss not to spotlight two great pieces of journalism about Kinmen: the first is this 20-minute documentary from the New York Times, which does a great job at visually capturing the island and its unique role in Cold War history; the second is an article by the Taiwanese journalist Amber Lin (who is also my grad school classmate), which includes some fascinating details of China's outreach campaign through politicians, temples, and schools. I especially love the end of Amber's piece, which highlights the Beishan Broadcasting wall, a massive speaker system on Kinmen's beach that used to broadcast propaganda messages across the Strait. The speaker is still in use today, though at a much more tolerable volume, and plays songs by famed Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng.

I should mention another characteristic of Kinmen, as I'd come to find out, is a relative looseness when it comes to planes taking off on time—or at all. Though the island is a quick, 50-minute flight from Taipei, when I went to the Kinmen airport for my Monday-morning return flight, I saw the morning's departure times flanked by the character 取消 (qǔxiāo, cancel). Because of fog over the Strait, Kinmen's one-terminal airport simply canceled a slew of flights, not even bothering to delay some of them. With no other option, I stayed in Kinmen another two nights. Thankfully my friends and I had the pleasure of being guided around by our resident Kinmen expert, our friend Ari, who previously spent a year on Kinmen teaching English as a Fulbright fellow. Thanks to his recommendation, we had two meals at an Indonesian restaurant that almost defies the concept of a "dive." This "restaurant" is the one-woman operation of 張阿姨 (Auntie Zhang), an Indonesian chef who serves up whatever you want (and whatever she feels like giving you) in her honest-to-God living room. The best chicken curry I've ever had!

Chinese Learning Corner

Every time I run into one of my favorite teachers, 林老師 (Teacher Lin), our interactions follow a delightful routine. I give the normal student-to-teacher greeting: 老師好 (Lǎoshī hǎo; Hello teacher!) or 早安 (Zǎo ān; Good morning!) and she responds by saying the exact same thing...except with the correct tones.

What does this look like? Something like this:

LAOSHI hao! laoSHI hao!

ZAO AN! zao AN!

Teacher Lin is one of the more committed teachers to the art of correcting students' pronunciation, a welcome but at times frustrating experience. Why is it frustrating? Because, in Mandarin and other tonal languages, you can intuitively know how a word is supposed to sound while still saying it incorrectly. Each word has a particular tone—and in Mandarin, there are four unique tones, in addition to a neutral one used for particles—and while they can change, the tones themselves are almost never dropped.

老師好 (Lǎoshī hǎo) is three syllables: a low tone (known as the "third tone"); a high, steady tone (the "first tone"); and then that low "third" tone again. But if speaking quickly, the words just come out of my mouth sounding incorrect.

For native English speakers, tones are particularly challenging because, in English, a change in tone tends to correspond to a change in emotion, but in Mandarin, tones are core to meaning. Whether you're sad, angry, or happy, 老師好 is always third tone, first tone, and third tone. A wrong tone will always disrupt your meaning and, at best, make your Mandarin sound hopelessly foreign, but sometimes the difference is exceedingly important. My favorite example of this is the words for "buy" and "sell." In Mandarin, "to buy" is 買 mǎi (third tone) while "to sell" is 賣 mài (the falling "fourth tone"). That slight difference in tone totally changes the meaning of what you want to say.

So every time I say good morning to Teacher Lin, I remember how lucky I am to have someone constantly sharpening my tones. As we students often say to each other, the only thing worse than a Chinese teacher correcting your tones is when they stop correcting them. (That means they've given up on you!)

Odds and Ends

1.

It is late April, which means the Philadelphia 76ers are on their way to blowing yet another winnable playoff series. I am almost numb to it at this point, but their latest flop seems almost too stupid to be true. While clinging to a 5-point lead with under a minute left in New York, a comedy of errors led to the Knicks regaining the lead and cementing a 2-0 lead in what looks like it could be a short series.

As careful readers of this newsletter know by now, I mostly avoid talking about my city's dreaded basketball team. Despite having one of the best players on the planet in Joel Embiid, who mere months ago scored SEVENTY points in a single game, every 76ers playoff appearance continues to look like that scene from The Simpsons where the guy keeps stepping on a rake.

I just simply cannot with this godforsaken team anymore.

2.

I had the pleasure last week of having lunch with Joshua Freeman, the eminent historian and translator of Uyghur poetry. We are all indebted to Josh for translating Tahir Hamut Izgil's magnificent Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide, which I actually mentioned in my first-ever newsletter last year.

As an aspiring political scientist, my interest in understanding Xinjiang comes mainly from a desire to study how the Chinese government's theory of ethnicity informs the kinds of brutal policies it has and continues to implement there. But there's no point in conducting that kind of analysis without an understanding of the culture Beijing's policies are stamping out. Thanks to translators like Josh, we can continue to celebrate artists like Tahir and others who have either had to flee their homeland or remain in Chinese detention.

In the spirit of celebrating that work, I wanted to include a poem, titled "Elegy," that I've been thinking a lot about recently. Its author, Perhat Tursun, himself an eclectic, controversial writer whose work often challenged traditional Islamic mores, was jailed in China in 2018. Here is "Elegy," as translated by Josh Freeman:

“Your soul is the entire world.”

Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

Among the corpses frozen in exodus over the icy mountain pass, will you recognize me? Our brothers

we begged for shelter took our clothes. Pass by there even now and you will see our naked

corpses. When they force me to accept the massacre as love

Do you know that I am with you.

After three hundred years they awaken and do not know each other, their own greatness long forgotten,

I happily drank down poison, thinking it fine wine

When they search the streets and cannot find my vanished figure

Do you know that I am with you.

In that tower built of skulls you’ll find my skull as well

They cut my head off just to test the sharpness of a sword. When before the sword

our beloved cause-and-effect relationship is ruined like a wild lover

Do you know that I am with you.

When in the market men with tall fur hats are used for target practice and a man’s face draws out in agony as a bullet cleaves his brain, and

before the eyes that look to find the reason of their death the executioner fades and disappears,

reflected in that bullet-pierced brain’s fevered thoughts will be my form, just then

Do you know that I am with you.

In those times when drinking wine was a greater crime than drinking blood, do you know the taste of the flour ground in the blood-turned mill? The wine

that Alishir Nava’i deliriously dreamed took its flavor from my blood

In that endlessly mystical drunkenness’s farthest, deepest chambers

Do you know that I am with you.

March 2006, Xihongmen, Beijing

That's all for this week, everyone! Expect another newsletter in your inbox very soon—and, this time, from outside of Taiwan (!!) Stay tuned!