#11 What It's Like to Learn Chinese at ICLP in Taiwan

Greetings from the United States! After 16 hours in the air, a little over an hour at the baggage claim, and a three-hour drive home, I made it back to Philadelphia.

This past year has produced a lifetime's worth of memories (and areas of reflection), but I'll save that for a later newsletter. This will be the first of three posts wrapping up my time in Taiwan. For this edition, I wanted to describe my classes and the culture at the International Chinese Language Program (or ICLP), the language school in Taiwan where I’ve been enrolled since September. In later posts, I'll give some final thoughts on my experience in Taiwan and then, as a bonus, I'll talk about my two-week trip through China!

But first, ICLP!

Before I applied to study at an intensive Chinese language program, I benefited from reading reviews and blogs that students in my position have written. Given that my time at ICLP is over 😦 I thought it would make sense to give back. If there’s a student out there like me, wondering if ICLP or a similar program is for them, hopefully this post will be useful to you. For that reason, this post will be a bit longer than my other posts.

A bit of background

Before entering ICLP in September, I completed a two-month Chinese program at National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu (pronounced “SHIN-joo”). I got the sense before (and after) completing that program, which was run through an American nonprofit (American Councils for International Schools), that NTHU’s program was relatively new. While the university itself is fairly renowned within Taiwan, its reputation mainly stems from its STEM programs, though its Chinese department had recently started an exchange program with the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. So while there is a robust Chinese department and teaching program, it is relatively new.

When I began the program in Hsinchu, I had just completed second-level Chinese at Georgetown (equivalent to taking four semesters of the language), but my true level was probably a bit below that. Though Georgetown’s teachers are excellent and certainly gave me a boost, I arrived in Taiwan with fairly mangled tones and only a moderately better ability to recognize Chinese characters. (I’ve mentioned this in a previous post, but mastering the tones of Mandarin Chinese is one of the more challenging aspects of learning the language as a native English speaker and needs to be drilled almost to the point of obsession.)

In Hsinchu, the program of about 20 total students was divided into three levels: each using a version of National Taiwan Normal University’s A Course in Contemporary Chinese textbook. After an oral placement test, I was assigned to the intermediate group, where I felt reasonably comfortable but recognized quickly how serious my deficiency with tones was compared to my classmates. During our four hours of classes, my tones were corrected relentlessly. Most times, I could comfortably repeat the tone correctly, but with a few particularly difficult tone combinations, I struggled to even do that. (A recurring challenge for a lot of learners, including me, is pronouncing 美國 Měi guó, which is the word for America. The tone combination is: low tone, rising tone.)

By the time I entered ICLP’s program in September, I had gained much more confidence with recalling tones and could reliably correct myself or at least have a better sense of when I messed up. (Not even knowing your tone is wrong is the worst place to be!) I also had expanded my vocabulary, which was already a strong suit for me. My listening ability and grammar still needed a lot of reinforcement, but by then my vocabulary was quite strong for someone at my level. Or, I should say, I could at least speak about some historical or political subjects that probably made my Chinese sound more advanced than it was (or is).

Starting at ICLP

In September, following a written and oral placement test, I was placed in ICLP’s fourth level, though I should also clarify that at ICLP, the idea of "your level" is a bit flexible. For the first five levels, ICLP has a fairly standard curriculum with each student taking four courses, including a mandatory "core" class and a one-on-one class that reinforces the material from that class.

Occasionally, students will have their core class be at one level but take electives that are a level above or below, depending on either their interests or skills where they need extra practice. (For example, some heritage speakers may come in to ICLP with fantastic speaking and listening skills, but need to develop their writing and character recognition. For me, it was sort of the opposite: my character recognition was fine, but my listening and speaking skills were far less developed.)

ICLP's internal course catalog lists eight levels, though once you enter the sixth level, there are no longer required classes and the structure becomes much more individually tailored to a student's core interests. (I'll explain more about this later!) The school runs on a quarter system with a long, month-long break between the fall and winter quarters and shorter breaks between the other academic terms. Usually, students advance a level per term, so if you enter in the fall quarter at Level 4, like me, you would finish the spring quarter having taken courses at Levels 4, 5, and 6.

In the Fall quarter, almost all of my classmates were either graduate students or upperclassmen with the vast majority having learned Chinese for 4-5 years. At that level, each student's core course is geared around a common textbook, Talks on Chinese Culture (TOCC). A group class (or 合班課 hé bān kè) discusses the material and grammar structures from that textbook. The one-on-one class is used to shore up any misunderstandings from the group class and advance some of the material. My two electives this quarter were Taiwan Today and Chinese News All Around I, both of which I absolutely loved. Every class has 3 to 4 students in total and is taught entirely in Chinese, though occasionally teachers will use English to explain the finer points of a grammatical topic. ICLP also maintains a strict policy on only speaking Chinese inside the building, which everyone tends to respect.

Talks on Chinese Culture

Like some of ICLP’s other more famous textbooks, TOCC is an adaptation of an older textbook, originally produced for students at Yale, though its material is frequently updated. Each chapter takes the form of a lecture on some aspect of Chinese culture, history, or politics. Some students found the topics quite boring—the discussion of currency exchange rates during World War II certainly won’t win many fans—but I actually really enjoyed the structure and most of the content. Before and after the “lecture,” the writers include a dialogue between two students, who in their conversation repeat many of the themes and highlight the key vocabulary of the chapter.

TOCC was the first textbook I’d ever studied to read like something a native speaker might actually consume. Its language is much more formal, which annoyed some students, but it significantly increased my ability to read news articles and communicate about more abstract topics. I also appreciated TOCC even more in hindsight once I started reading actual Chinese scholarship and realized that the textbook’s discussion of Chinese history (though perhaps not pinpoint accurate in a rigorous, historical sense) does reflect trends of thought among Chinese scholars.

Though this textbook is the same for all Level 4 students, each ICLP teacher seems to have substantial discretion* over how they teach it. A common thread is using class time to review grammar patterns and, at least in my class, I found that we focused more on grammar in my group class and a bit more on the actual content of the lectures in my one-on-one class.

(*A note about this: while in my experience, it seemed as if teachers had almost total control over how to organize and assess their class—with different sections of TOCC having different schedules and structures—this seems to be less true at lower levels where ICLP more strictly controls the structure of the class.)

Taiwan Today

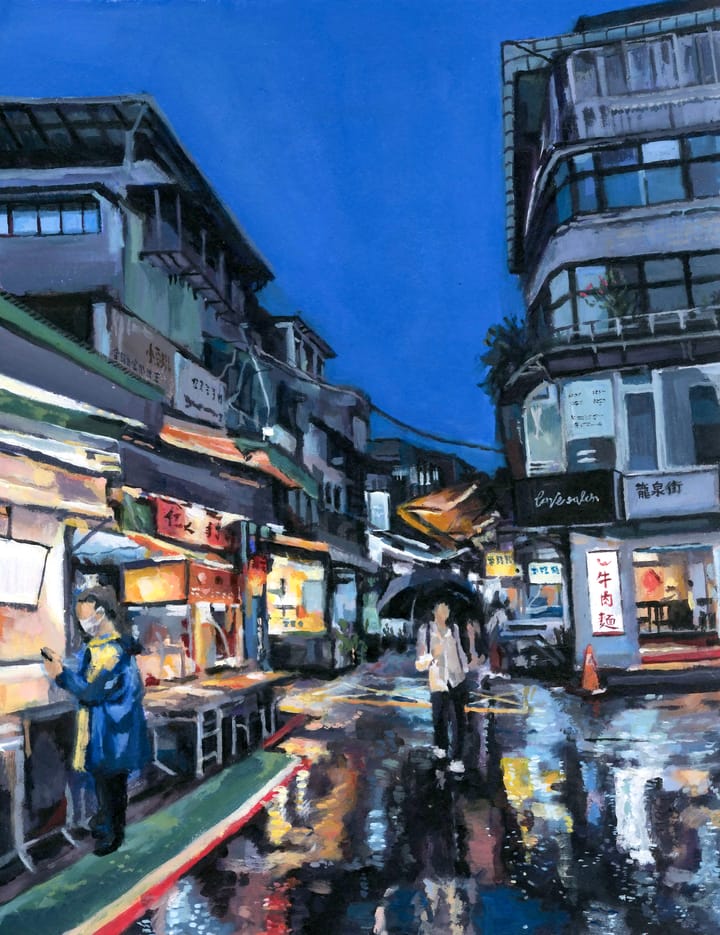

This course used a textbook that is a bit difficult to categorize. Its first few chapters cover fairly basic topics, including Taiwan's parks and night markets. I also found the grammar quite basic at the start, not necessarily encountering many new structures or concepts. But, over time, the textbook advances in difficulty to the point where later chapters touch on political issues between China and Taiwan along with the status of Taiwan's indigenous peoples.

I mostly enjoyed this class primarily because of my teacher. I've written before about Teacher Lin's commitment to correcting tones, but I really benefited from her focus on this aspect of learning. We frequently read aloud from the textbook and were forced to correct ourselves over time. Because the actual content of the textbook was not too difficult, certainly not as difficult as TOCC, I was able to focus more on speaking and listening.

Chinese News All Around I

ICLP has quite a few different classes built around news articles, all with different emphases. This one used an eclectic set of articles on topics ranging from Serena Williams arguing with a referee at the U.S. Open to a Japanese guy who marries a virtual anime singer. (Seriously!) All the stories describe real news events, but have been edited substantially for students.

I loved this class! My instructor, Teacher Zhang, had a terrific personality and provided a lot of context to the articles. He also focused a lot on tones, which helped me in particular. The textbook itself shrewdly includes a lot of words, most of which are drawn from Classical Chinese, that regularly appear in news articles. Just like in English-language articles, Chinese news has a set of jargon unto itself that takes time getting used to. (For example, in everyday speech, you would use 他 的 tā de to say "his," but some news articles may use 其 qí instead. Learning these words formally was a big advantage when I eventually started reading longer news and academic articles.

When things get really hard!

For the winter quarter, I moved up to Level 5 courses, which are centered around ICLP's Thought and Society textbook as a Core class. I also took an introduction to Classical Chinese, which turned out to be one of my favorite classes, and another News class—this one focused on listening to news reports, as opposed to reading articles.

Thought and Society

This book is the fulcrum of ICLP's curriculum and alumni from even decades ago still will mention it. Like TOCC, the book is divided into several essays on topics in Chinese culture, such as health, parochialism, and religion/spirituality, but the vocabulary is far more extensive and abstract.

It also includes a number of four-character expressions and idioms, some of which are allusions to Chinese literature. My favorite example is 扶不起的阿斗 Fú bù qǐ de ādǒu, which essentially means a "good-for-nothing" person. It's a reference to "A Dou," a figure from Chinese history who is remembered for his ineptitude.

Most students will tell you that preparing for Thought and Society was a brutal time. The vocabulary, in addition to being abstract and occasionally literary, is not repeated much within the text, making it more difficult for the student to remember. A good deal of the vocabulary list also deals with near-synonymous words, which need to be properly delineated. (A good deal of my Thought and Society final exam was devoted to separating words that share a character, such as 忽略 hū lüè and 忽視 hū shì, which are not synonymous but similar enough to be used interchangeably by unsuspecting students.)

This class really kicked my butt, though I certainly became a better student of Chinese because of it. I found the vocabulary incredibly difficult to remember, though much of it does reappear in academic texts and news articles. It is clear how highly ICLP values the class based on the fact that many students in their Level 6 quarter will essentially "re-take" Thought and Society as a one-on-one course, not because they necessarily need the reinforcement, but because the book itself demands that much attention.

You can also see the influence of Thought and Society in, quite frankly, the way that many ICLP students speak and write, as some of Thought and Society's more colorful expressions become a staple of ICLP students' formal essays (and less formal banter). Case in point: me saying 扶不起的阿斗 to everyone I meet!

Introduction to Classical Chinese

You might be surprised to know that a good deal of ICLP students take a course in Classical Chinese. The program seems to take pride in the fact that they offer it in the first place and teach it in modern Chinese (as opposed to some university courses in the West, where English is mostly used to explain the grammar.)

Why should someone want to learn Classical Chinese? It's a good question! Learning it is not quite like learning Shakespearean English or Cervantes' Spanish. Classical Chinese is functionally a different language from modern Mandarin with very different grammar structures, usage, and vocabulary. Of course, if you're a scholar, learning it is unavoidable because most written Chinese material prior to the 20th century is in some form of Classical Chinese. But even if you have no interest in formally studying China, learning Classical Chinese has some modern utility. A lot of idioms—many of which appear in the Thought and Society textbook—come from Classical Chinese.

For me, these benefits far outweighed the cost of taking Classical Chinese, which boil down to "occasional tedium." Because the class is fundamentally a class in translating from Classical Chinese to modern Chinese, it can be tedious to go character by character, line by line, imbibing new rules and structures to go on top of the ones from modern Chinese you already know.

But well, sue me, I loved it! This class was really fun, not least because Teacher Cui was a very patient guide through some challenging material. It made some idioms come alive now that I understand their original meaning and gave me a taste of what a typical middle school or high school student must be dealing with in Taiwan, where the debate over how much emphasis to put on Classical Chinese as a school subject still rages.

News & Views

This textbook has some useful vocabulary and grammar structures, though the content of its assembled news stories is a bit outdated. (Most news articles involving the United States date to the George W. Bush administration. There's even a unit about Libya and Qaddafi before, well, you know!) That being said, I don't think the recency of the articles is as important as their educational value and, on that point, News and Views does do a great job tackling a variety of topics, from economic sanctions to mental health. Like Thought and Society, this textbook is one that I've returned to frequently just to review the grammar and vocabulary.

The home stretch

My spring quarter at ICLP was my most demanding in terms of homework, but also the most intellectually satisfying. Unlike previous quarters where my one-on-one class supplemented a core class, in this quarter (roughly equivalent to ICLP's Level 6), I had no core class and used my one-on-one class to read a series of essays about ethnic policy in China (which is the focus of my academic research back in the United States).

At this stage, ICLP is rather generous when it comes to letting students design and arrange schedules that suit their interests. I had classmates take courses devoted to Taiwan's defense policies, the Chinese epic Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and even Taiwanese Hokkien, the native language of many Taiwanese whose ancestors immigrated from southern China. In short: you have a lot of flexibility, though the curriculum office (and teachers themselves) are firm in not placing students beyond what level they think you are capable of handling. (I learned this the hard way when I was shot down for a few classes I originally wanted to take.)

The classes I ended up taking were a blast—and a terrific capstone to my yearlong experience learning Mandarin in Taiwan.

Written Translation

This class is what it says on the tin: translating written English into Chinese. In my professional career, I imagine I may have to do some translation in the opposite direction, but the usefulness as a student of rendering English into Chinese is the way it reinforces vocabulary and grammar I may have learned, but never fully grasped.

One aspect of this class I really loved was Teacher Sun's use of extraordinarily different materials for translation. Some days, we'd have to translate the equivalent of a lover's quarrel in extremely colloquial English. Other days, it would be part of a formal United Nations report, requiring a similar register of formal Mandarin. Near the end of the course, she also had us watch videos and write out translated captions, which tested not only our language ability, but demanded a kind of creative editing to make the captions short enough to fit on the screen.

Lu Xun

The name "Lu Xun" is well known to any student of literature. He's only one of the most famous 20th century Chinese writers, beloved in equal measure for his inventive short stories and incisive criticism of China's feudal history and traditional beliefs. In this course, we read several of his short stories and wrote essays reflecting on them. Though we did occasionally discuss his use of vocabulary (and it appeared on our final exam), the class mostly took the form of a high school Literature class, where we interrogated the themes and biases of each story.

One fun feature of this textbook, which compiles many of Lu Xun's more famous stories, is that it uses not just Traditional Chinese, but the older form of many characters, making it a good preview of the difficulty in reading slightly older materials. As an example, in modern Traditional and Simplified Chinese, the character 才 cái is rendered the same way, but Lu Xun uses an older, less common form: 纔.

China's Peril and Promise

This textbook, a collection of essays and short fiction from early 20th-century Chinese writers, turned out to be a hidden gem! I didn't know much about the course before enrolling, but ended up getting the opportunity to read writers like Ba Jin, who I absolutely adore, along with more essays by Lu Xun, which neatly complemented his short fiction.

One-on-One Class: China's Ethnic Minority Policy

I've written about this before, but my main academic interest is in the ethnic policy of China—essentially, how China defines ethnicity, how that idea of ethnicity is reflected in policy, and why/when that policy turns explicitly assimilationist or punitive, as in Xinjiang and Tibet.

It had long been a goal of mine to read Chinese ethnic policy scholarship in the original, so I proposed this course and was lucky enough to be paired with an excellent teacher. We reviewed essays from authors I'd been familiar with—either because of their ideas or from reading their translated writings—and all came from different perspectives. Some were expressly pro-government in their stance and pushed for a harsh, assimilationist policy, not dissimilar from what China adopted in Xinjiang in 2017. Others pushed for a relaxed approach. And, in the final weeks of the course, we read a full government white paper, which gives the official Party history of Xinjiang.

From an intellectual standpoint, this course was the culmination of everything I've been working toward since I started studying Chinese. It felt immensely gratifying to finally read these scholarly articles in the original and, more than anything else, it made me appreciate ICLP's willingness to let students design classes to fit their own interests.

So...how much did I improve?

That's the $1 million question. The short answer is: a lot! Even someone sleepwalking through a year at ICLP would improve by quite a bit, but I think I really did push myself to improve my tones and reading ability, particularly by switching to using Traditional Chinese midway through the program. My listening ability did still lag behind my peers and, though my speaking improved substantially, it still is riddled with pronunciation errors and unnatural phrases.

I do feel far more confident beginning and continuing conversations and, more importantly, motivated to continue learning! If anything, I'm scared to stop, not wanting to regress from the standard I set for myself at ICLP.

I hope this newsletter answered at least some questions you may have about my experience and what the last year has been like. And, worry not, two more newsletters are on the way soon.

Thank you for staying with me this far. I promise to make these last ones worth it for you.

(And for the kind few of you who've supported me with cold, hard cash—first off, thank you, and second, I've gone ahead and turned off that subscription tier, so you should not be charged again.)

Thanks all and enjoy the start of another blazing hot summer.

Dan